Mind over matter...or trying to

Course in Humanities: Fortnight #11

I’m back.

Apologies for the delay, but I could barely hold my head up without my nose dripping like a faucet and then I had one of those weeks.

But, as people often say, better late than never.

Today I’m sharing my thoughts on the eleventh fortnight of our adapted version of Ted Gioia’s Course in Humanities.

You can find previous parts of this course at the end of this post.

For now, we’ll discuss:

a) Ancient Roman art and architecture.

b) Haydn Symphonies: 45 (Farewell), 94 (Surprise), 104 (London).

c) Marcus Aurelius: Meditations, and Epictetus: The Enchiridion.

Ancient Roman art and architecture

Roman art (6th century BCE - 5th century CE) was heavily influenced by the Etruscans, who dominated much of Italy before Rome rose to power, the Greeks and, consequently, Egypt and the Near East.

The Etruscans had an elaborate cult of the dead, with big necropolises and funeral games (believed to have inspired gladiator combats). They made high-quality metalwork, detailed sarcophagi, tomb sculptures and murals.

The Romans, taking a few pages from Greek tradition, built upon Etruscan culture and art, creating their own, even more elaborate, sarcophagi, wall paintings (fresco technique with watercolors on wet plaster), mosaics, statues and sculptures (decoration, status and propaganda).

Roman art often displayed nature, political figures and mythological themes. It leaned towards realism, practicality and functionality.

The term Roman architecture usually refers to what they built between the late 6th century BCE and the 4th century CE, however, most sites and constructions we have from that period are dated after 100 CE, when the Empire had grown considerably and accumulated a lot of resources.

This is not to be confused with Neoclassical architecture, which is a style inspired by Greek and Roman architecture that began in the 18th century in Europe.

Like art, their architecture was influenced by the Etruscans and the Greeks, especially when it comes to columns.

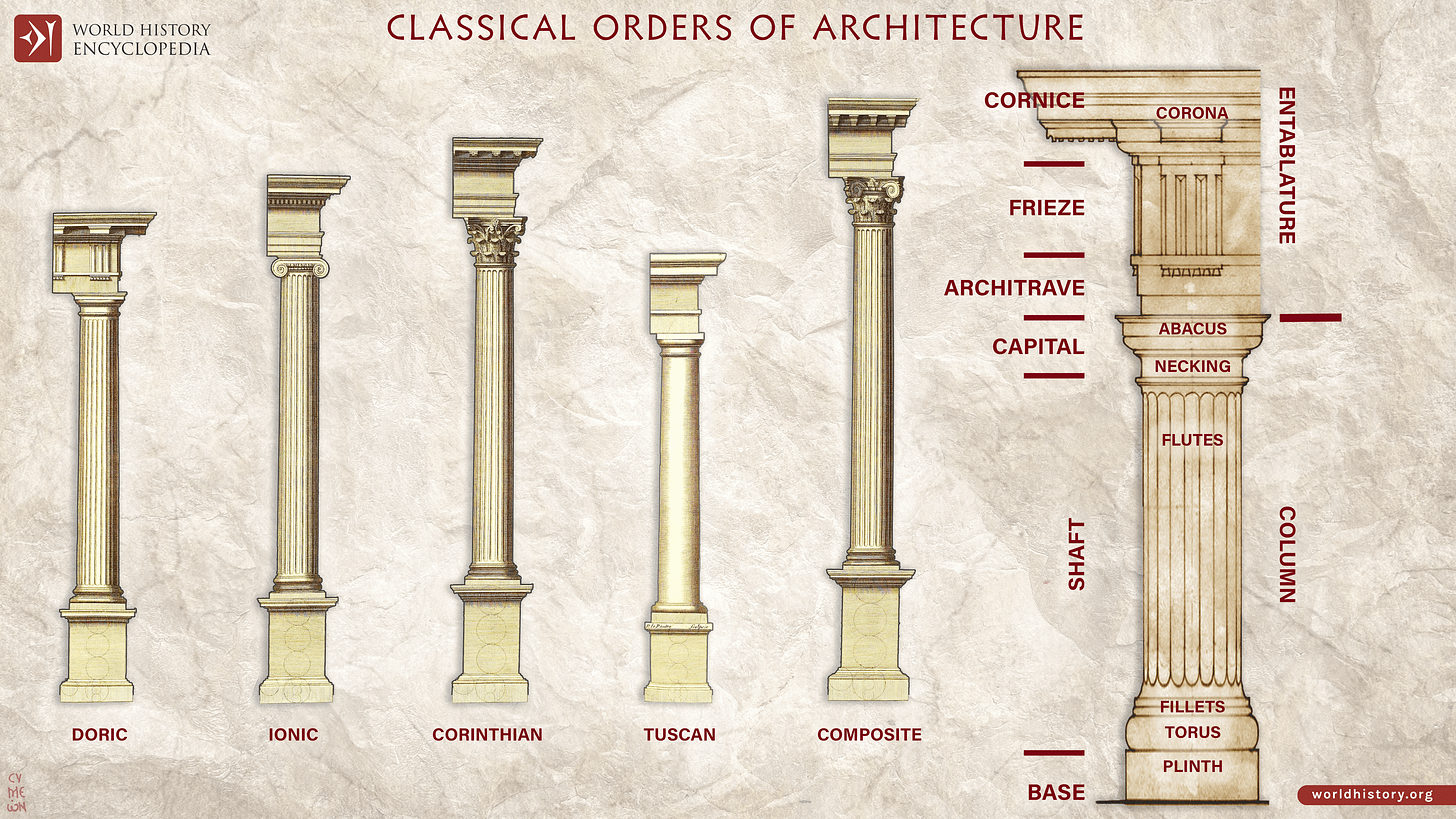

In addition to the traditional Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns, the Romans developed their own capitals and cornices, sometimes even mixig styles (Composite order). We also can’t forget about the Tuscan column, which was an adaptation of Doric column. Romans liked columns so much they continued to be used as decoration long after this kind of sctructure was no longer needed for support.

Besides the domes, arches and vaults themselves, Romans are known for their aqueducts, bridges, temples, theatres/amphitheatres and walls. The most popular materials were stone, brick and concrete.

Contraty to popular belief, the Romans were not the first to build with concrete (as usual, Asia, more specifically the Near East, is in the lead). They did, however, use volcanic materials to create a revolutionary recipe for concrete and were the first civilization to base their architecture on it, making it widespread, resistant and durable1.

But the Romans did not limit themselves to adapting pre existing ideas.

Not only did they produce mesmerizing and highly functional buildings, they advanced engineering and created technologies for housing and public hygiene at a scale never seen before in Europe (and subsequently lost for several centuries). It’s worth mentioning their baths and latrines, under-floor heating and piped hot and cold water.

Haydn Symphonies

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809) was an Austrian composer, often called the “Father of the Symphony” or the “Father of the String quartet”. He had a humble beginning and, after a while struggling as a freelance musician, was able to build a successful career as a composer and music director (apparently he even mentored both Mozart and Beethoven).

I enjoyed the three symphonies Gioia recommended, 45 (Farewell), 94 (Surprise), 104 (London), but my favorite was nº 94.

As soon as it began, a ballet came alive in my mind. A forest waking up with the spring, a troop of childlike, mischievous rodents playing tricks on bears, swans, geese and deer.

I can see the sets, costumes, choreography… too bad I don’t have the resources or the skill to share it with you.

Stoicism

Stoicism is an ancient school of thought founded by Zeno of Citium (c. 334 – c. 262 BCE), a wealthy merchant of Greco-Phoenician background who became a philosopher in Athens after a shipwreck around 300 BCE. It was quite popular in Greece and Rome for about half a millennium and has seen a resurgence in modern days.

Stoics divide their studies in three interconnected parts (physics, logic, and ethics) that encompass all of life and the universe. To them, philosophy is the practice of virtue according to Nature, the only way to achieve eudaimonia.

In Stoicism, the kosmos is the sum of all its parts and everything that occurs does so according to its own laws (determinism). Human life is but a fleeting, miniscule event in the grand scheme of things, destined to end and return/disappear into a cosmos that is forever renewing itself.

Given the ability to think (reason), humans can either accept what happens to them (action instead of reaction) and be happy or uselessly try to rebel against Nature and allow themselves to suffer.

The Enchiridion by Epictetus (and Arrian)

Epictetus (c. 50 – c. 135 CE) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery and, with permission from his master, studied Stoicism under Musonius Rufus. He obtained his freedom sometime after the death of Nero (68 CE) and began to teach philosophy in Rome until he was banished by Domitian and moved to Greece.

Like Socrates, Epictetus didn’t leave his philosophy in writing. It was up to one of his pupils, Arrian, to save his master’s teachings to posterity.

I decided to put Arrian in parentheses, despite the fact that he indicates his mentor as the “author” of The Enchiridion, because it feels as if the book is his. The Enchiridion reads a lot more like a student’s personal notes than the actual teachings of Epitectus.

In case you want to see what I’m talking about, try reading the Discourses, also written down by Arrian. The mode of expression, style, approach and range of subjects of those two texts are so different I can’t help but to see Arrian copying down a lecture (Discourses) vs. Arrian reflecting on and summarizing what he had heard (Enchiridion).

That being said, what is the Enchiridion about?

Basically, it’s a manual on how to live like a Stoic.

Assuming nothing external2 (hunger, pain, sickness, grief, loss, etc.) is good or bad, everything that happens to you is an opportunity to practice virtue, which leads to happiness.

You should act (virtuously) instead of reacting to things, after all, you can only control your thoughts (what you make of things around you) and your behavior.

You should avoid being impatient (learn to endure) and incontinent (exercise self-control). You should also dedicate yourself to study and reflection, but never forget that practicing what you believe in is miles above believing.

The Stoics have a very negative view of passion, which can lead to suffering (like vices do), but that doesn’t mean one should be apathetic or insensitive. You’re supposed to be in control of your emotions and reason must dictate how you live.

Naturally all of this easier said than done.

I had the opportunity to try this philosophy during the last couple of weeks and I can tell you I’m definitely not a Stoic.

While I agree life (and all its troubles) is just temporary and worrying about things I can’t change is a waste of time and energy, I can’t see the ordered and predetermined cosmos Stoics believe in.

Life and the universe look utterly random and chaotic to me — and I actually like them that way. Freedom is harder to deal with, but much more exciting than Fate.

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (121 – 180 CE) was Roman emperor (161 to 180 CE) and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last emperor of the Pax Romana, a period of relative stability for the Roman Empire. Despite that, he did not have an easy life.

His father died when he was four and he was adopted by emperor Antoninus Pius as heir, a position he did not covet, but did his best to fulfill. While he got to enjoy the best of everything money could buy, he still had to watch eight of his thirteen children die (the rest didn’t last long after he was gone).

He spent most of his time as emperor at war and his rule was marked by death3. He also learned very quickly that there was little he could do to change Rome for the better amidst all the power struggle surrounding him.

It’s no wonder he was so attracted to Stoicism and admired Epictetus’ teachings.

If Nature and its laws dictate everything that happens, if Fate says things are the way they are, his powerlessness was not his fault — it was all just an opportunity to endure and persevere.

His Meditations, in a Pythagorean fashion, are a journal where he reflects on his conduct and encourages himself to keep following stoic principles.

The themes of legacy and being remembered after death seemed to occupy his thoughts a lot. He was worried about how to behave, manage his emotions and interact with the world around him. There is also a more gentle, charitable, kind of socratic side of him that tries to understand and forgive.

I’m pleased to say this book is a great read.

When you study History, famous people can often feel like something other than human.

Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations are so relatable, simultaneously simple and complex, that I had a lot of fun looking for the man behind the words — the person who believed, feared and hoped to live up to his expectations for himself.

If you don’t know much about Stoicism, I strongly suggest reading the Enchiridion and Discourses before this book or at least pick an annotated edition of Meditations to prevent feeling a bit lost (since it’s a journal, it makes no sense for Marcus Aurelius to explain things he already knows to himself).

This is it for today.

I hope you’ll join me for next fortnight.

In case you haven’t read them, here are parts One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, Seven, Eight, Nine and Ten.

For comparison, our concrete, which might last a century if well-made, is way more inert than the Roman’s, which reacts to the environment and repairs itself, lasting for hundreds, even thousands of years.

An external factor is anything outside of one’s control.

The Antonine Plague or the Plague of Galen lasted from 165 to 180 CE and killed between 5 to 10 million people, including Marcus Aurelius himself, who died in a military camp. There is no genetic evidence of its pathogen, but it’s believed to be smallpox.