Today I’m sharing my thoughts on the fifth fortnight of our adapted version of Ted Gioia’s Course in Humanities.

You can find previous parts of this course at the end of this post.

For now, we’ll discuss:

a) The sculpture and architecture of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

b) Bach: Cello Suites.

c) Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics and Poetics.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) was an Italian sculptor and architect who was active during the High Baroque (c. 1625-75) — one could even say he was the artist who elevated the movement to highs never seen before (seriously, the guy could make marble look like flesh and about to move).

He is considered the best Western sculptor of the 17th century, perhaps the best in the world, and left his mark all over Rome1 and the Vatican City (he worked for every Pope who reigned during his career and many high raking members of Church and nobility). He also created paintings, drawings, and works for the theater.

Some of his most famous pieces are Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, in the Cornaro Chapel2, Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius (check out Homer’s Iliad and Virgil’s Aeneid), Rape/Abduction of Proserpina (featured in Ovid’s Metamorphoses) and Apollo and Daphne (also featured in Ovid’s Metamorphoses).

Cellos Suites

And now, music… or something we haven’t figured out a proper name for: the Cello Suites by Bach.

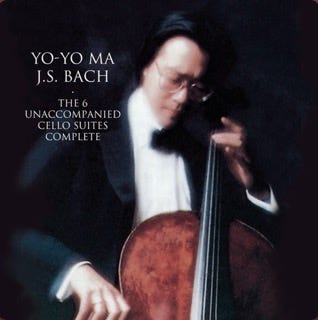

I tried a few *cough* versions3 and my favorite right now is Yo-Yo Ma’s (1983). I found it to be the exact blend of elegance, speed and passion I needed.

I'm definitely biased on this matter.

To me, the cello is the sexiest instrument there is. Excuse me distinguished gentleman with their grand pianos and cool rock stars with their drums and electric guitars, I'm hanging out with the cellists.

I don’t know when I started to associate cellos with passion (any instrument can be used for that). All I know is that, whenver I listen to a well composed and performed cello piece, I get this tingling and lustful (in the broadest sense of the word) feeling in my whole body, like I could bite life with all my teeth and take a huge chunk out of it.

In Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonata, Pozdnyshev, who has deeply flawed and problematic notions regarding women, sex and relationships, complains about music, saying it can be powerful enough to alter one's internal state to a foreign one (he murdered his wife due to jealousy of a musician she is close to).

While I find Tolstoy’s take to be very dramatic and pessimistic, I agree that music can have an effect over our emotions and state of mind (our actions are something else entirely).

Feeling the music, going along for the ride, is probably the best part of listening to it.

Aristotle

Aristotle (384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath. His work covers a wide range of topics (natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology and art) and gave rise to a tradition or school of thought instrumental to the development of modern science. Sadly most of his writtings were lost, despite the fact he was revered and copied extensively by both Christian and Muslim scholars throughout the ages.

The first thing I must say before going into this reading assigment is that Arsitotle’s work is vast and interconnected — he frequently builds upon what he has already written and uses certain terms with very specific or particular definitions.

That’s why I urge you to pick an edition in which the translator clearly explains the parameters adopted or the distinction between the original word and the one they chose to represent it, especially if you’re not familiar with Aristotle.

The second aspect of his work I would like to point out is that it has aged much better than most of his contemporaries (incluing his mentor, Plato). So if you're worried about reading something far removed from reality today, don’t.

Unlike Plato (and Socrates in Plato's dialogues), the natural philosopher in Aristotle strives to find the universal in the world around us (something that applies to us as humans) instead of leaning too heavily on particular opinions or beliefs (religion or Forms, for example) that they hope will apply to everyone.

Last but not least, one of Aristotle’s best habits is “reviewing bibliography”. He routinely refers back to what others have said or written so that he can build his case, which not only gives you a better sense of where his arguments are coming from and the larger cultural frame he belongs to, but also makes him feel more modern and approachable, standing in the shoulders of those who came before him.

That being said, let’s talk about the Nicomachean Ethics and Poetics

Nicomachean Ethics

Possibly dedicated to his father or son (both named Nicomachus)4, it’s the most widely read of Aristotle's ethical treatises.

Like Plato and Socrates, Aristotle wonders what is the best/right way to live. He comes up with, in my humble opinion, a very good, though not perfect, answer.

In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues the ultimate end of all human activities is Happiness, which we desire for its own sake (as opposed to things we desire for the sake of something else).

In that sense, the goal of the Ethics is to determine the best way to achieve happiness and is closely linked to Politics (the happiness of the polis).

“Eudaimonia” is a Greek word that means "happiness" or "flourishing", and, in Aristotle’s work, it involves a sense of fulfilment or success that goes beyond a mere feeling of contentment or well-being.

While we can agree that humans, as species, are unified in our pursuit for happiness, we tend to disagree on what it entails. Nevertheless, we do strive to be happy.

Every creature has its own defining characteristics — ours is rationality. When properly exercised and developed, our ability to know and choose leads to excellence, which in turn leads to Happiness.

This is fundamentally different from Socrates’ ideas.

Socrates assumed that knowing the Truth would lead to the correct behavior. Aristotle recognizes that knowing is not enough — one must choose to act on that knowledge repeatedly until it becomes part of them. For example, I know, without a shadow of doubt, junk food is bad for me, but I keep eating it because I have a bad habit (a vice).

To Aristotle, “aretē” (often translated as excellence or virtue) is the habit of choosing the (Golden) mean between extremes. For example, courage is excellence in a scale of fear — too much of it leads to cowardice, to little, to rashness.

He goes on about many types of virtues and corresponding vices, which can be moral or intellectual. I would like to highlight his ideas on Justice.

To Aristotle, Justice is also a kind of human excellence and it’s tied to the notion of reciprocity — you give and take according to literal equity5 (some might call it corrective justice) or proportional equity (distributive justice).

Justice exists in two spheres: law and nature. This divide is similar to what we saw in Plato/Socrates’s dialogues, but with a key difference. While Plato stands by the Form of Justice, a concept that belongs in a Realm beyond the material world, Aristotle looks for an answer in Nature.

Aristotle’s natural justice, the idea that certain behaviors or actions are right or wrong regardless of background (universality vs. relativism), is not to be confused with Christian theology or theory of natural law, according to which there is a Creator of all that exists, including the rules of natural justice.

Aristotle’s Nature simply is. His ideas of fair and unfair arose from human nature (rationality), not from faith or religion.

Something else to keep in mind, especially for Fortnight #11 (Stoicism), is Aristotle’s views on passion6 and pleasure, which also falls into that spectrum we must scan to avoid excesses and find the appropriate amount/type.

I think a lot of what he wrote is great advice and, while I believe the purpose of Life is to keep existing, I like the idea of making happiness our goal.

If I try to picture the happiest version of myself, I see an active and curious woman, living at a slow pace somewhere safe and close to nature (but still close enought to the city to enjoy its perks and travel every now and then to a place I’ve never been), without worring about money and spending my days reading, writing and learning all the things I haven’t been able to dedicate myself to: drawing, paintings, playing instruments and so much more.

Yes, I know, my goal in life is to be high middle class retiree (maybe all those people who said I was born an old lady were right after all).

Poetics

This is a short, incomplete text, probably meant as lecture or part of a lecture, that focus on the poetic art — its essential attributes, forms and goals.

I personally didn't get much out of it, but it’s still a highly relevant historical text that shaped the Western view on art, being the first of its kind.

Some people think of it as manual for poets (playwrights), others think of it as theory of poetic art/tragedy or even an apology of Greek Tragedy, excluded from Plato's ideal city. I took as a good example of how art can contribute to human flourishing.

I like Aristotle’s take on mimesis (imitation) — art represents7 the natural world and our lives are better because of it. Plato’s dismissal of poetry that doesn’t “serve” his ideal city (mimesis doesn’t take us to the Forms) always seemed like such a waste of human potential to me.

This is it for today (Substack is telling I’m near email length limit).

I hope you’ll join me for next fortnight.

In case you haven't read them, here are parts One, Two, Three and Four.

I recommend taking some time to see his fonts, tombs and monuments.

A masterpiece in design, sculpture and architecture that, according to Bernini himself, was his “least bad” work.

Actually seven, but I’m still looking for more.

It’s likely NE was designed as lecture or supporting material to Aristotle’s students, not for publication.

Some translations might use the term equality.

Sometimes translated as anger.