Today I’m sharing my thoughts on the second fortnight of our adapted version of Ted Gioia’s Course in Humanities.

You can read the first part of our course here.

For now, we’ll discuss:

a) Ancient greek sculpture.

b) Schubert’s Winterreise and Joni Mitchell’s Blue.

c) The Iliad by Homer.

PS.: Gioia skips the Iliad and goes straight to the Odyssey due to page limit and time constraints, but we’ll read both of them.

We were also supposed to talk about greek lyrics (Lattimore collection), but I forgot to finish the book (the Iliad drew most of my attention), so we will discuss it next fortnight with the Odyssey.

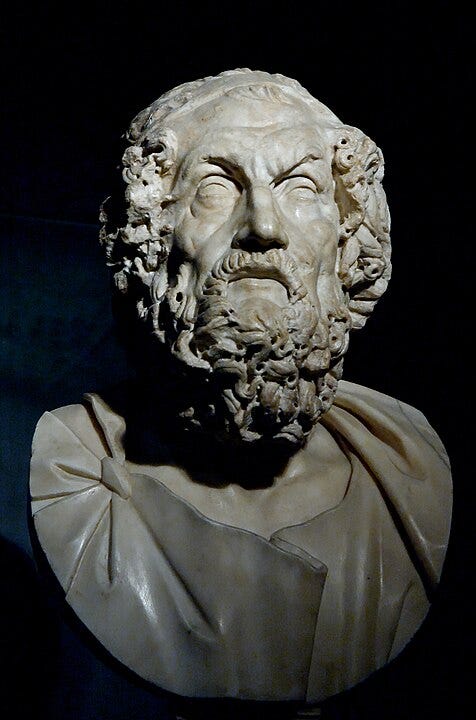

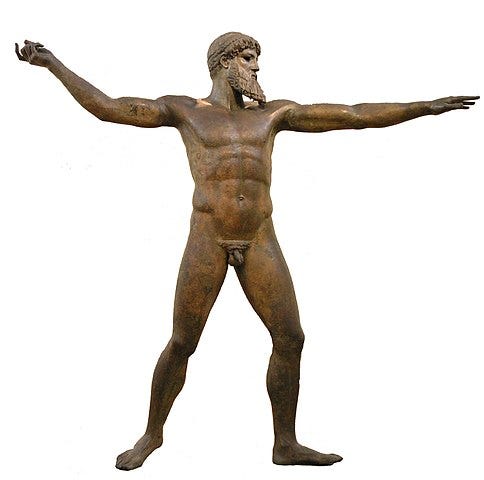

Ancient Greek Sculpture

I consulted multiple sources and websites regarding art in Ancient Greece, but the focus of the research was largely oriented by Art The Definitive Visual Guide published by DK.

As many of you are probably aware, globalization is not a recent phenomena. The Mediterranean allowed intense cultural exchange between Europe, Asia and North Africa, and Greek culture was highly influenced by Egypt and the East.

It’s worth mentioning the legacy of the Minoans1, whose culture was absorbed by the Mycenaeans. The age of the Mycenaeans, which ended around 1100 BCE, is remembered in myths and legends that shaped greek tales of heroes and gods (such as the Trojan War).

Still, the Greeks were able to create an artistic tradition of their own, spread through the conquests of Alexander the Great, later inspiring the Romans and the descendants of their empire.

Traditionally, scholars divide greek art in three periods: Archaic (c. 7002 to 480 BCE), Classical (480 to 323 BCE) and Hellenistic (323 to 31 BCE).

Even in the early stages of its development, greek sculpture was focused on the human body, particularly the male nude and draped female.

This might be a natural consequence of their religious beliefs. Greek gods are way more human than a lot of the deities in ancient mythology and are portrayed in similar form to athletes and war heroes.

Already during the Archaic period, artists began to distance themselves from rigid poses and anatomical disproportion. Over time, the search for the perfect representation of the human/divine body reached unprecedented levels of detail.

The sculptures were usually painted (pigments fade over time) and made of stone and bronze (larger pieces), which were fairly easy to find at the time. Small sculptures were often made with other materials.

Music (and lyrics)

I adored Schubert’s Winterreise.

Franz Schubert (1797-1828) was born in Vienna and learned to play piano and violin from his father. He was incredibly prolific, especially considering he died at 31, and, though he never fully broke way with the classic tradition, Schubert is considered to be one of the greatest romantic composers.

He created pieces for both public and private performances, but is mostly known for his contributions to lieder. Lied can be roughly defined as a type of German song, designed for solo voice with piano accompaniment, that was popular3 in the romantic period.

This genre of music, usually sung at home or for small audiences, was deemed secondary to opera and performances on the grand stage (orchestra included), but it’s closer to us and the way we express our feeling through music today than most of the big productions you'll find at Opera Houses and Theaters, regardless of how amazing they are.

The Winterreise Cycle is undoubtedly one Schubert’s best works. Inspired by common themes in germanic poetry, particularly Wilhelm Müller lyric poems, it’s tragic, dramatic, dark and captivatingly beautiful.

I listend to two versions of this cycle.

The first one, recorded by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (voice) and Alfred Brendel (piano), felt more intimate, delicate, fragile even. The second, also sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, was accompanied by Gerald Moore, one of the 20th century greatest pianists.

Moore’s hand sounds more intense, heavier and sure. While I'm drawn to Brendel as an artist, I felt that Moore matched Schubert’s composition and Fischer-Dieskau's performance better.

My experience with Joni Mitchell’s Blue was weird.

I felt like I was listening to the background of pop music, which I guess is a testament of how successful she is.

Roberta Joan "Joni" Mitchell (1943-) is a Canadian-American singer-songwriter and painter.

She is usually associated with the 1960s folk music, but often interwove multiple genres, like pop and jazz, creating a unique style that, along with her lyrics, made her one of the most influential artists of her generation.

It kind of makes me sad I’ll never experience her work as a true novelty since I’m so used to the themes and techniques she help to create and popularize, but at least I can tell where they came from.

By the way, my favorite songs on Blue are All I Want, Little Green and Carey.

The Iliad

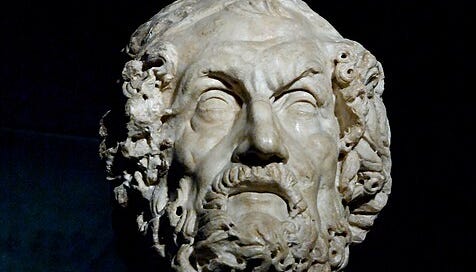

Heading towards the main course, I think it might be useful to talk briefly about Homer.

There is a lot debate about the authorship of the Iliad and the Odyssey. No one really knows who Homer was or even if there was a Homer at all.

Was Homer a bard who performed original poetry or pieces they learned from their masters? Was Homer a group of artists working together or separately that eventually created a monumental epic poem? Did Homer dictate their work to a scribe? Is the Iliad (and the Odyssey) just one version of a story told over and over for centuries and finally put to “paper” (papyrus scroll), in which case Homer would be the scribe(s) themselves?

We don’t know and, unless some revolutionary discovery is made by historians and archeologist, scholars will probably continue to discuss the matter ad infinitum.

For the sake of simplicity, whenever I say Homer, just assume I’m talking about the culmination of ancient greek culture and epic poetry, transmitted orally throughout centuries and somehow preserved to posterity, and not necessarily an individual.

On a different note, I think it’s also worth talking about the Trojan War — fought between a coalition of Mycenaean/Greek states and the Trojans (plus allies) for Helen of Troy (originally Sparta) and the honor of King Menelaus (left by his wife Helen, who fled with prince Paris).

To the ancient greeks, the Trojan War was a historical event that took place in the age of heroes (remember the Mycenaeans we talked about earlier on this post?). Most people were already familiar with it, so you could say Homer’s greatest achievement was how they told a widely known story and not the story itself.

Nowadays most scholars agree the Trojan War was a myth or legend, possibly inspired by tales of grandeur of an age gone by and by people/places that might have been real4, but different from Homer’s descriptions — the Iliad has a peculiar anachronic blend of past and present5.

Last, but not least, the Iliad (named after the city of Ilium/Ilion, also known as Troy, after the people who lived there) only deals with a small portion (a few days, plus dislocated references to the past and future) of the myth of the Trojan War, which supposedly lasted a whole decade.

So, what is the Iliad about? The answer lies in the opening lines of Book I:

Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath

of great Achilles, son of Peleus,

which caused the Greeks immeasurable pain

and sent so many souls of heroes

to Hades, and made men the spoils of dogs,

a banquet for the birds, and so the plan

of Zeus unfolded — starting with the conflict

between great Agamemnon, lord of men,

and glorius Achilles6.

In case you are a new reader or long absent one, you might enjoy Professor Elizabeth Vandiver’s course The Iliad of Homer (The Great Courses). It’s structured in twelve 30-minutes lessons and discusses the authorship, themes and main characters of the Iliad. I listened to the audiobook (no additional material, provided with the full course) and found it to be accessible and useful, though she tends to get a bit caught up on certain topics.

If your unable or unwilling to commit six hours to the course or simply do not like the classroom approach, I recommend reading Peter Jones’ introduction7, as he discusses many of the same themes more succinctly.

Back to the poem, the Iliad starts when Agamemnon (Menalaus’s brother) takes way Achilles concubine, which he received as spoil of war, to mitigate the loss of his own (her father, a priest of Apollo, tried to ransom her, Agamemnon denies, the sun god sends a plague to the greek army and he has to give her back).

Achilles has no personal stake in the Trojan war — he went there solely to achieve immortality through glory or fame (kleos). When Agamemnon takes Achilles’ prize, distributed in acknowledgement of his honor or merit (timê), he also takes away his motivation to fight, so it’s not strange he refuses to join the battle (which I found perfectly understandable).

But Achilles doesn’t just abstain from fighting — he asks his mother, the goddess/nymph Thetis, to plea to Zeus to make his fellow soldiers temporarily lose in battle to the Trojans so they’ll learn how important he is (honestly, he sounds like a spoiled brat trowing a tantrum).

Zeus grants his mother’s wish; the Mycenaean/Greek army has to beg Achilles to come back (he initially does not as he is contemplating the possibility of trading glory in battle for a long life in peace); his friend Patroclus goes in his place and is killed by Hector, the greatest trojan hero; Achilles goes mad with grief and starts killing everyone in his way, including Hector, whose body he defiles; King Priam goes to Achilles and begs for his son’s body back; Hector’s funeral marks the end of the story (You won’t find the horse or the sack of Troy in this book).

The summary above doesn't even begin to cover everything that happens on the Iliad, but I believe it’s enough to prompt discussion.

I think one of Homer’s best decisions was to make the Trojans so relatable — is there a better way to get your audience to care about an enemy defeated by their ancestors?8

My favorite part of the Iliad is the contrast between Hector (my favorite character) and Achilles.

Hector is the embodiment of humanity, not to mention much more likeable and well-rounded than the protagonist. He is honorable and a great warrior, but flawed and limited. He a prince, a son, a brother, a husband and a father. He is afraid, but finds a way to encourage his troops and keep going despite the fear. He criticizes, but forgives. He fights for duty and love. He carries a huge burden, the hope of all his people, and when he falls, we know Troy will fall as well.

Achilles is something other than a man. The son of goddess, he stands apart as his own entity. He not only knows his fate — he gets to choose between a long life in peace and a short life that leads to eternal glory, something no other mortal in the Iliad is allowed to do (demigods incuded). He is self-absorbed and, when goes rampage, unleashing his fury on the world, he is even less human than the gods themselves (the gods can be really petty and frustrating — I can't stand Athena).

Ultimately, Achilles finds his humanity back and pays the price for his revenge.

I found myself constantly comparing the two heroes and wondering what is the measure/worth of a man’s life.

Some people might find the text repetive or formulaic, especially when it comes to the scenes (meals, getting ready for battle, combat) and the way the verses are structured (they keep coming back to the same point/information9).

However, that’s expected considering the poem, which has more than 15 thousand lines10, was supposed to be commited to memory and performed live (you would need near perfect memory to do that without the help of repetition and formulas)11.

One thing I do find to be incredibly strange is that the Iliad features no sea battles, despite the fact both sides are maritime powers12. The description of land battles is unrealistic (they end too quickly, often with a single blow), but I think Homer was able to capture the chaotic and destructive nature of war.

In the end, the Iliad is a book I would recommend (urge) to anyone — great literature at its finest form.

I also had the pleasure of rewatching Troy (2004), directed by Wolfgang Petersen and written by David Benioff. It was based on the Iliad by Homer and Posthomerica (“after Homer”) by Quintus Smyrnaeus, an epic poem in Greek hexameter verse that focuses on the events between the death of Hector and the fall of Troy.

The creators took a lot of liberties when adapting the story, which is understandable considering the theatrical cut only lasts 2h43 (it’s believed the Iliad alone took three days to perform). Yet, the movie is enjoyable and aged quite well, maybe because it was made two decades ago.

One of the most noticeable differences was the removal of the gods and their antics, giving the story a more historical than mythological feel. I like that Helen and her relationship with Paris are merely an excuse for war rather than its motive.

Movie Hector is just as humaine and perhaps even more awesome than I pictured in the book. Achilles, on the other hand, was kind of a letdown (I wanted him to be more impressive, godlike, but this version fits well with the realistic approach they had going on).

The portrayal of battle was very homeric — chaotic, gruesome and messy, but with plenty of opportunity for the heroes to shine. However, I must say they could have spent more time training the extras (a lot of the clearly don’t know what to do with their shields and weapons).

Overall, it was a nice complement to the experience.

This is it for today. I hope you'll enjoy this fortnight’s material as much as I did — I’m even considering doing a deep dive, book by book, of the Iliad.

Is that too much or would you guys be interested in reading it?

See you soon.

The Minoans probably originated somewhere in modern day Turkey.

There is quite a debate regarding the precise date, some say it was closer to 800 BCE, others pin point 650 BCE as the beginning of the Archaic period.

Schubert’s music and lyric poetry is not to be confused with popular folklore songs, which were a great source of inspiration for romantic artists who idealized the past and contributed to create nacionalist pieces.

There is place many believe to be the location of the ancient city of Troy. You can watch this quick TED-Ed video to learn a little bit about it.

Or the present 3000 years ago.

This is version, translated by Emily Wilson, is not the one I read (see footnote bellow). I merely choose it because it seems popular, and therefore recognizable, right now. I will not recommend a translation of the Iliad — there many available and you should take some time to chose the best one for you.

In Brazil, this introduction is inclueded in Ilíada/Homero; tradução e prefácio de Frederico Lourenço; introdução e apêndices de Peter Jones; introdução à edição de 1950 E. V. Rieu. — 1ª ed. — São Paulo: Penguin Classics Companhia das Letras, 2013. I do not recommend Rieu’s introduction — it feels outdated.

I would have liked it more if the Trojans were different from the Greeks. In the Iliad, they speak the same language (Troy’s allies have their own), pray to the same gods and have the same culture (even funeral practices).

Peter Jones refers to this as “ring composition”. Ring composition can be described as a literary device, common in ancient Greek and other oral/orally-influenced literatures, that uses symmetry to indicate/highlight the unity/relevance of an episode. The first element corresponds to the last, the second to the next-to-last, and so on.

The Iliad is a long poem (15,693 lines), divided into 24 books (scrolls) and written in dactylic hexameter. Dactylic or heroic hexameter is a form of meter or rhythmic scheme frequently used in Ancient Greek poetry. It contains either a long syllable followed by two short syllables or two long syllables.

Naturally some variation must have occurred with each performance.

Troy was strategically located near the Dardanelles Strait, which connects the Aegean Sea to the Black Sea.

This fortnight's discoveries are interesting! I think I'll go ahead and listen to the music, your description of it was so compelling. As for the Iliad... I have to admit. You've moved me. I think I'm going to read the book again but watch the movie too! I think you're right, although I wouldn't say it's anything "great," I do think it's worth more time and appreciation than I gave it, certainly. Also about Homer's identity, I never knew that! It's like Shakespeare all over again. Haha.